By Stephanie Kalina-Metzger

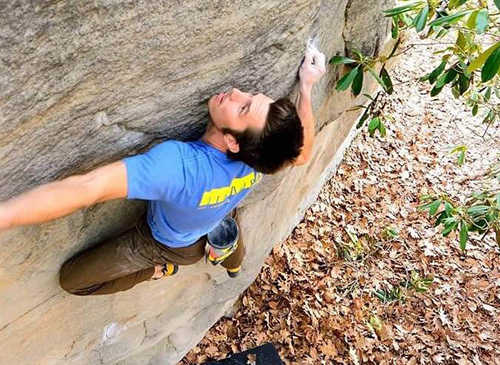

Three “Dynamic Haptic Robotic Trainer” systems lined up and ready to train medical residents at Cedars Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. Photo: Provided.

Engineers are naturally problem solvers and, as such, are often pioneers of innovation. Those who choose to become professors don’t always stop inventing. Take the case of Scarlett Miller and Jason Moore. Both are professors of engineering at Penn State who identified a problem and adopted a goal to fix it through a Happy Valley-based business they founded called Medulate.

“We combined our expertise and examined the impact that training played in the medical profession,” said Miller.

Through advanced engineering, we have the potential to positively impact patient safety.”

What Miller and Moore discovered through doctor interviews is that central venous catheterization was a top issue when it came to human error. For those unfamiliar with the term, central venous catheterization is when a catheter is placed into a large vein to deliver fluids, deliver medication or take samples. Central lines are generally placed in a large vein in the neck, upper chest or groin. Also ranking high in human error was needling, from subcutaneous (under the skin), to percutaneous (passing through the skin) and IV injections.

The pair discovered during their research that medical professionals who performed needling less than 50 times were prone to error. This led the team to the conclusion that the problem could be traced back to surgical training, which in turn, led to the development of Medulate.

“What we learned is that the procedure is simple when you’ve done it a lot, but the biggest burden is learning how to do it on a patient. There’s a steep learning curve when a real patient isn’t being worked on,” said Miller.

Moore, who oversees the Precision Medical Instrument Design Lab, used his experience with robotics to begin designing new training technology.

Introducing the LT100 and LT2000

According to Moore, Medulate’s resulting LT100 simulator now trains medical professionals on percutaneous and subcutaneous needling procedures, as well as IV injections, by providing haptic feedback to mimic forces inside the human body. Students receive data on the accuracy of needle placement, the angle of insertion and the steadiness of that insertion. The training is self- guided, eliminating the cost of an instructor and offering feedback on performance over time.

The LT2000 simulator further replicates ultrasound-guided central line placement using 50 unique patient profiles. As the software also gives feedback over time, students can track their performance.

Miller said that the simulators are a win-win for both the patients and the users to reduce failed insertion attempts and offer something that a cadaver can’t, which is feedback.

Help from within and without

But the simulators and research needed to get Medulate off the ground were expensive, so Miller and Moore went searching for outside funding from a variety of sources. In 2015, the pair received an R01 grant from the National Institute of Health, which is awarded for mature research projects that are hypothesis-driven via strong preliminary data. Those who win the grants receive up to five years of support, with a budget that reflects the costs required to complete the project. This NIH R01 grant was renewed in 2019.

“What we learned is that the procedure is simple when you’ve done it a lot, but the biggest burden is learning how to do it on a patient. There’s a steep learning curve when a real patient isn’t being worked on.”

Penn State, in an effort to support its College of Engineering faculty entrepreneurs, also helped the project along by awarding Miller and Moore an ENGINE grant, to assist them in developing their simulation training idea through a partnership with Hershey professor Dr. Sanjib Adhikary. In 2019, the pair went on to compete in the Ben Franklin Technology Partners TechCelerator program, which helps startups de-risk their business ventures. After pitching their idea to a panel of judges, they went home with the top prize of $10,000.

Making an impact

Looking to the future, Miller and Moore hope that their simulators will end up being the gold standard when it comes to ensuring that medical students are effectively and inexpensively trained.

“The thing that motivates us most about Medulate is the impact we can have on human lives. Through advanced engineering, we have the potential to positively impact patient safety,” said Miller.