By Cara Aungst

The CHIPS and Science Act provides $52.7 billion for American semiconductor research, development, manufacturing, and workforce development.

The CHIPS and Science Act provides $52.7 billion for American semiconductor research, development, manufacturing, and workforce development.

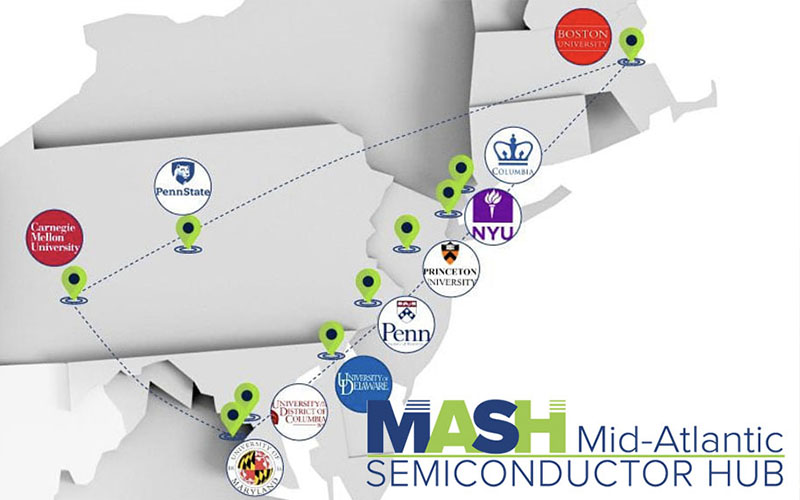

Semiconductor use is skyrocketing, used in everything from military equipment to mobile phones to climate-friendly lighting and is the lifeblood to the new boom in artificial intelligence. They are projected to become a trillion-dollar industry by 2030, but only 12 percent of the market share is currently manufactured in the United States. That’s a problem, and one that Penn State and Mid-Atlantic Semiconductor HUB (MASH) is determined to take on. On May 22-23, Penn State hosted a MASH workshop, with representatives from 10 Mid-Atlantic universities, government and industry, to identify industry-academia-government partnerships that will position the U.S. for technology and workforce leadership in semiconductors and microelectronics.

Semiconductor and chip technology have been tremendous strengths for Penn State for several years, visible in our national rankings as No. 1 and No. 2 for materials science and materials engineering.

“The solution is big,” Penn State’s president Neeli Bendapudi said at the opening of the event. “But if not us who, if not now, when?”

MASH was created by Penn State in answer to the U.S. government’s CHIPS (Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors) and Science Act, which was signed into law on Aug. 9, 2022, and is formed around the concept of regional hubs, which will be focused on promoting research, development, and commercialization of semiconductor technologies in specific regions of the US.

“Semiconductor and chip technology have been tremendous strengths for Penn State for several years, visible in our national rankings as No. 1 and No. 2 for materials science and materials engineering,” Lora Weiss, senior vice president for research, said.

The two-day event brought representatives from Mid-Atlantic schools like Princeton, Columbia, the University of Pennsylvania and Cornell, along with government agencies and industrial partners, all focused on one thing: how to leverage collective expertise to create solutions.

Here are some takeaways from the event:

The Mid-Atlantic region has what it takes to create solutions for this issue.

The Mid-Atlantic Semiconductor Hub (MASH) was created more than a year ago by Daniel Lopez, a Liang Professor of EE at Penn State University and Director of Penn State Nanofabrication facility. “The technical expertise and resources in semiconductors concentrated in the area is unique in the world. By coordinating and sharing resources across MASH we could have a unique impact in workforce development and semiconductor manufacturing.”

“There is such a wonderful infrastructure,” Gerald Lopez, Director of Operations and Business Development & Singh Center Associate Director, University of Pennsylvania, said, adding that the Mid-Atlantic region of the U.S. has the highest density of laboratories and universities in the world.

The United States has been behind China and other countries in production for years, but Covid amplified the supply chain issues and shortages.

In addition, with more than 60 million who call the region home, it offers a workforce pipeline to fill the jobs needed to manufacture semiconductors.

Solving semiconductor production is a national security issue.

The United States has been behind China and other countries in production for years, but Covid amplified the supply chain issues and shortages that can result when semiconductors aren’t available. “It’s an economic security issue and a national security issue,” Weiss said at the event.

Workforce development is a major piece of the puzzle, and it starts with education.

Experts projected that 300,000 direct jobs will be created and the supporting supply chain will create another 1.7 million jobs over the next 10 years.

The CHIPS and Science Act represents billions in income, but it also showcases the best of American R&D: an opportunity to empower entrepreneurs, develop STEM talent in underprivileged areas, and expand the geography of innovation.

Where will the talent come from? It requires education and access, National Science Board Vice Chair Victor McCrary said. That means increasing funding for community colleges, increasing STEM education in K-12 classes and creating access for talent from all demographics. “One weapon we have is geographic and ethnic diversity,” he said. “We just have to leverage it.”

“We don’t need to compete, but team up”

The event built in coffee breaks, Q&A sessions and boxed lunches around round tables — all created to spark conversation and collaboration. “This is one of the most open meetings I’ve ever attended,” one attendee from Cornell told me, noting how everyone from lab techs to industry leaders sat and talked, ideating about how to work together.

Penn State is a clear leader in materials and creating collab opportunities

I got the opportunity to tour the Millennium Science Building with a group of industry leaders on Wednesday morning, and it was cool to see Penn State’s materials dominance from an outside perspective. It was unabashedly optimistic, gritty and collaborative — working tirelessly to find solutions. A big part of the CHIPS and Science Act proposal (which hasn’t been released yet) is said to focus on infrastructure, and Penn State did a great job of showing off its powerhouse of knowledge and assets.

One of the speakers, Victor McCrary, made a connection to the days of Sputnik and the space race, and looking around that room filled with people brainstorming and collaborating, it wasn’t hard to see a comparison.

The CHIPS and Science Act represents billions in income, but it also showcases the best of American R&D: an opportunity to empower entrepreneurs, develop STEM talent in underprivileged areas, and expand the geography of innovation.

“This is what the future is all about,” McCrary said.