What makes Lasers for Innovative Solutions, LLC (L4IS), developer of LATScan, so interesting is perhaps what it’s not. While most startups inside Innovation Park’s Tech Center Incubator have been started by PhD-holding researchers, Ben Hall joined the U.S. Navy and served in Operation Iraqi Freedom before enrolling at Penn State. As a student, he spent more time working in the Applied Research Laboratory (ARL) than in his classes. The path that led to his big idea was even less traditional: when he was asked to cut corn root cross-sections for analysis, the task proved so boring and laborious that he decided to improve the process. Now, his invention–first-of-its-kind laser-driven 3D modeling–is changing how agriculture research is done around the world.

“I was working at ARL under Ted Reutzel (now director of CIMP-3D), doing very cool, interesting things,” Hall says. “And one day, somebody from the Plant Science Department asked if we could cut corn roots with a laser. They needed cross-sections that were about the size of a toothpick, and they’d been doing it by hand — cutting them, putting them into a vial, then photographing the cross-section under a microscope. They could only do 3-5 per hour, and they had about 20,000 samples to go. There was a huge bottleneck, as you can imagine. It was terrible.”

Dr. Reutzel tasked him with finding a solution. “I didn’t have a specific job — they gave me the weird stuff.” He experimented with laser cutting the samples and was able to turn out 11 per second — a massive increase from 3 per hour — but he still had to trudge across campus with all of the physical samples to get them photographed and analyzed. Then he had a lightbulb moment. “I could just imagine them here,” he recalls thinking.

Figuring out a “stupidly complex” problem leads to a surprising solution

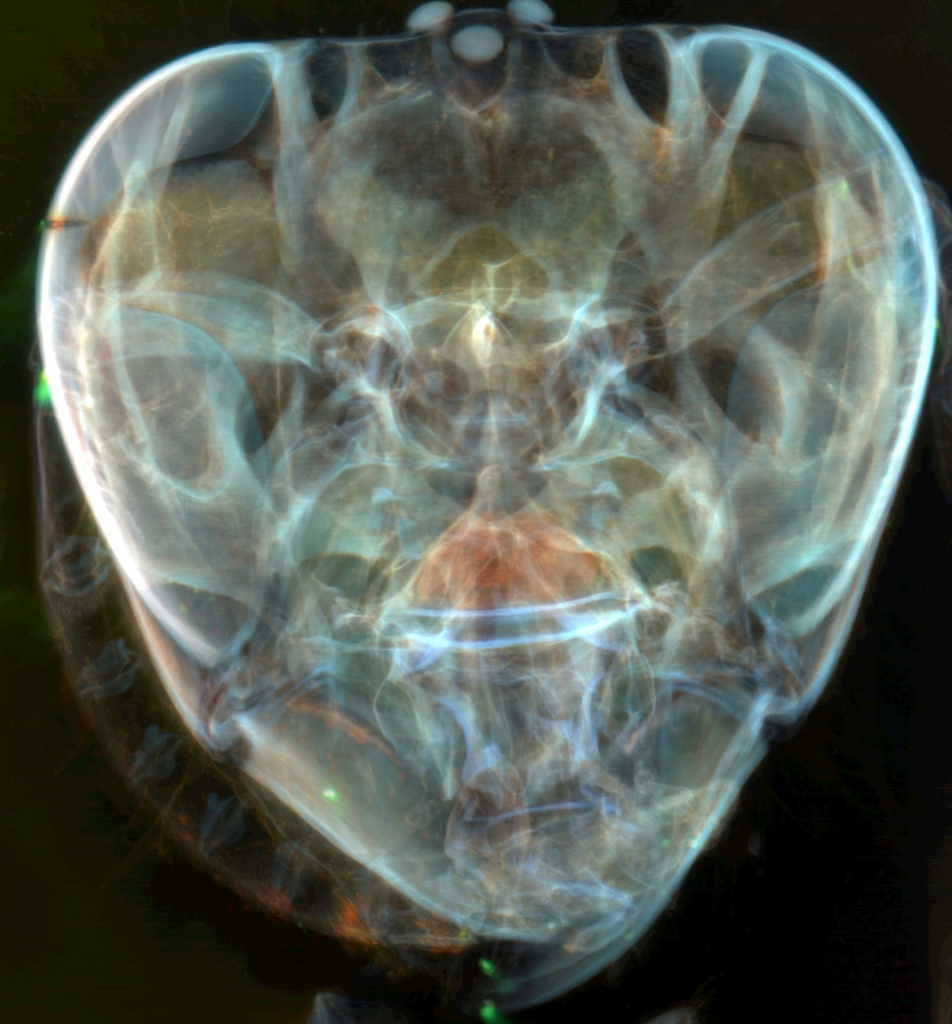

After a week of trying to figure out the “stupidly complex” problem, he decided to sweep the laser back and forth at 100x per second and record a video of the action with a high-powered zoom lens. “It looked like the root was traveling toward the camera, but disappearing as it hit the invisible laser sheet. The contrast was really, really high, and eventually, I realized that every video frame was a different cross-section of the root. After finding some programs to pull out the individual frames and digitally stack them, it turned out I had essentially created a rotating, 3D model of that plant. I remember my reaction: ‘HOLY CRAP, THAT’S AWESOME.’”

Not only was it a rotating 3D model of the plant, but it offered something researchers didn’t have before: a complete view of the interior of the plant, not just a single slice. It was novel data that apparently no one had collected before.

Ben Franklin TechCelerator helps L4IS make the jump to commercialization

Dr. Reutzel, along with Dr. Jonathan Lynch from the Department of Plant Science, encouraged Hall to patent his find. From there, he set out to start a company with Brian Reinhardt, a friend and Ph.D. student in the College of Engineering Science and Mechanics. He attended a Ben Franklin TechCelerator Bootcamp to learn some business basics and got a loan to buy equipment. “It was scary,” he says, “Putting all your eggs into one basket.”

As he created the business, he found more and more researchers in need of his laser-driven tomography as they analyzed genetic differences in plants, animals, and even human data. “You’d typically have to do huge volumes of samples to see trends emerge because of errors and uncertainties with current methods,” Hall says. “Not only can that be inefficient and slow, but there can be a lot of error-induced noise in the process when it’s done by hand.”

LATscan offered samples that were perfect, clean, and “super fast,” but Hall knew he needed to make researchers aware of the company. “Every so often, other startups in our building would push their equipment down the hall because they were packing it in. And I just kept thinking we were next.”

Fate and sweat equity = a contract with a multi-billion-dollar ag company

Fate and sweat equity intervened: within a year, they had a contract with a multi-billion-dollar agriculture company.

“The more we did, the better we got,” Hall says. Over the next few years, he worked with Penn State talent to create an AI program that did image analysis of 3-D models. And after that, the company got a contract to build and deliver their first customer-operated LATscan machine to the University of Nottingham in the UK.

That sale prompted them to focus on creating commercial LATscan machines for research facilities (naturally Penn State got one right away). And even though Hall says that the pandemic served up their “worst year ever,” 2021 brought an increase in demand as researchers realized the depth of data that they could study with their equipment. “Some people are changing their PhDs midstream based on the information they are getting from this analysis,” Hall says.

L4IS is growing again in 2022. In addition to keeping the lab in Happy Valley, Hall and his wife are moving to Seattle to join its biomedical business ecosystem and keep pushing the envelope on both sides of the country.

He says it’s a move that never could have happened without support from Penn State, Innovation Park, and Ben Franklin. “It’s really awesome, fertile ground for a startup,” he says. Hall also credits his co-inventor, advisor, and mentor Dr. Reutzel. “Ted is the single most important positive influence in my entire life,” he says.

Cara Aungst writes about industry, innovation, and how Happy Valley ideas change the world. She can be reached with story ideas and comments at Cara@AffinityConnection.com.